Get Inspired

Build the life you love. Learn more about fusioneering:

Posted on February 14, 2022 in Inspirational People

Few names are as synonymous with art, culture, and creative genius as that of Leonardo da Vinci. The 15th century Italian polymath created several of what can be considered “the most recognizable paintings in the world” (most notably, The Mona Lisa and The Last Supper) – and yet, only about 20 of his paintings have survived to the modern day… with many of them considered unfinished. The body of work may seem small, but the quality (including of the pieces Leonardo himself considered incomplete) speaks volumes. What’s more, like many of his High Renaissance contemporaries, Leonardo was interested in so much more than just painting: sculpting, architecture, engineering, drafting, science, anatomy, botany, cartography… the list goes on and on and on. Leonardo was a man whose foremost interest was knowledge, and whose chief work was in finding the incredible intersectionality between disciplines and schools of thought. A fusioneer.

Is there anyone alive in America who can’t picture the Mona Lisa? What about The Last Supper? These images maintain their wild fame half-a-millennium beyond their conception. Leonardo’s depictions of things like light, depth of focus, anatomy, and perspective forever changed the human understanding of painting and the arts. Da Vinci’s goal was to accurately depict the world as it was seen with the human eye, and this interest in producing the highest quality of realistic and enchanting works is what drove da Vinci to be so aggressively exploratory and curious in scientific matters. Verrocchio, the artist da Vinci had apprenticed under, had taught Leonardo extensively about art theory – but left Leonardo with questions of how best to render the imagistic depth, richness, and subtle imperfection of the real world. Without tools like cameras or complex measuring instruments, Leonardo was still able to achieve his lofty artistic goals – so well, in fact, that he is still widely considered the greatest painter of all time. How did he do it? The answer is an inspiring one, because the tools are available to us all: curiosity, observation, and persistence. Da Vinci tested most of his concepts – such as accurate planes of focus displayed by the human eye – simply through trial and error. He would set up a scene, observe and think deeply about what he saw, and then attempt to replicate it with the tools and techniques available to him. If no known technique would suffice, through laborious testing, he would invent a new one. When he had questions about geometry, lighting, anatomy, or form, he would test them, as a scientist tests a hypothesis.

Leonardo’s pursuit of beauty was as obsessive as his pursuit of knowledge. This is exemplified by one of da Vinci’s signature techniques, “sfumato,” (derived from the Italian word for smoke). Sfumato produced a realistic transition between colors, a blending akin to the blurred areas around a human eyes’ central point-of-focus. Da Vinci achieved this effect by painting numerous extremely thin layers of faintly-colored glaze on top of one another. A single layer of glaze might contain less than 10% of a colored pigment, and a single layer might only be as thick as a couple of micrometers… and, for reference, the average strand of human hair is about 70 micrometers thick. The technique can be observed around Mona Lisa’s eyes, giving them their famously mysterious and life-like appearance. It’s this incredible attention to detail and dedication to the craft that not only allowed da Vinci to advance the field of painting, but also led to overall advances in the human understanding of optics, vision, and physics.

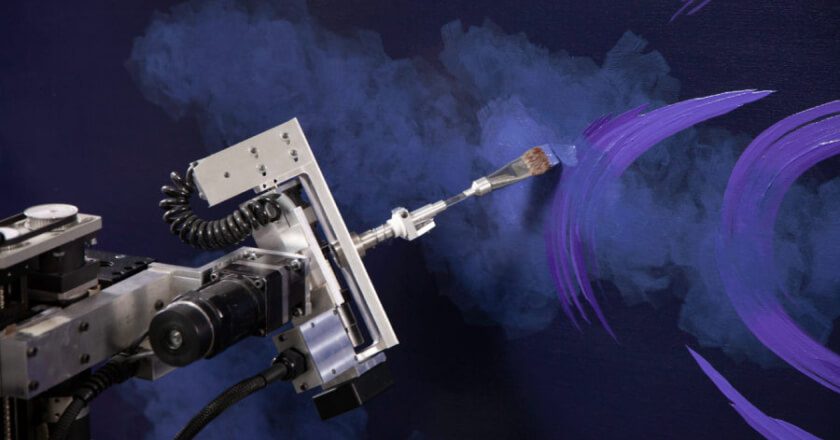

Related: Want to see how da Vinci’s extraordinary sfumato technique influenced Paul Kirby and Dulcinea’s work? Check out the creative process behind the 2010 painting, Swirling Timbers of Chaos.

Unlike in the preceding Middle Ages, in the period of the Renaissance, the studies of art and science were seen as intrinsically linked fields. We often think of da Vinci as an artist first and foremost, and while he would have considered the same of himself, in truth, he was employed most heavily as an engineer. Despite being a pacifist, Leonardo said in a 1482 resume letter to Ludovico Sforza, the ruler of Milan: “…having now sufficiently seen and considered the achievements of all those who count themselves masters and artificers of instruments of war, and having noted that the invention and performance of said instruments is in no way different from that in common usage, I shall endeavor […] for the purpose of unfolding to you my secrets, and thereafter offering them at your complete disposal…” Luckily for Leonardo, his designs for offensive weapons (which many historians argue were purposefully designed to be impractical) were never put to actual wartime construction.

Da Vinci never attended a university and was never given any formal instruction in Latin or mathematics. Because of this, his scientific endeavors – outside of his numerous practical inventions – were largely overlooked by the scholars of his day. Even his engineering successes, such as a system of modular and movable dikes to bar invaders from entering Venice, were considered financially impractical. Setbacks, criticisms, and the money-and-war-centric economics of his day never dissuaded Leonardo from his journey of curiosity and multidisciplinary discovery. Though his designs weren’t as functional as the man may have liked, da Vinci conceptualized the ideas of the helicopter, parachute, armored vehicle, and solar power cells, just to name a few. Da Vinci understood complex engineering principles vastly ahead of their time, and he utilized intricate systems of gears, ball bearings, pulleys, cranks, and hydraulics to conceive of or invent new machines the likes of which his time was entirely unprepared for. In addition to inventing wonders like a self-propelled cart that served as a precursor to the modern automobile, or an automaton knight that served as the precursor to modern robots (such as The Kirby Foundation’s own Dulcinea), da Vinci also felt the need to hide many of his advancements from the world around him. In regards to a system Leonardo devised to supply air to diving suits and theoretical submarine vehicles, he said in one of his notebooks, “…I do not publish nor divulge these by reason of the evil nature of men who would use them as means of destruction…” It is true that da Vinci was born ahead of his time, and it’s obvious that the nature of that unfortunate reality was not lost on the great man himself. For all his innumerable contributions to modern society, however, we are unquantifiably fortunate that da Vinci existed when he did, and strove to push the envelope of his era.

Leonardo the artist, or Leonardo the engineer? They aren’t separate at all. In fact, without one, the other wouldn’t even exist. Science and art were symbiotic tools to da Vinci; he would explore questions of the sciences with his artworks, and explore questions of his art through science. And both became stronger. Leonardo’s areas of study were not seen as opposing fields locked in separate rooms, but were, rather, all integral components of a single worldview. Every discipline that Leonardo held under his hat was just another gear, working together with, and relying on, all the rest. With every new endeavor da Vinci undertook, he drew on the background of all the things he knew across all the experiences he ever had. Every solution was built creatively, fusioneered together from a toolbox of seemingly disparate parts.

The secret of Leonardo’s capabilities and appeal was the hunger and respect he carried for knowledge. His most ambitious goal was not to produce works that would gain him fame and fortune, but rather simply to better understand and represent the world in which he lived. Moreso than an artist or engineer, Leonardo was a thinker and philosopher working to explore incredible concepts through visual media.

If we wish to create great things, across all disciplines, we must continually seek to understand the elements of our existence at the greatest depths of their construction. We must think unbridled by structural limitations. We must tear down the divides we have created within our own minds, that we may approach every scenario with our greatest creative potential.

We must be like Leonardo.

Leonardo da Vinci has been a colossal inspiration on so many lives – like that of Kirby Foundation founder, Paul Kirby. Paul was so moved by the life of Leonardo that he began his very own journey of fusing art and science – a path that would eventually lead to a new and unexpected journey of inspiring individuals through the power of art, technology, and creativity.

Are you interested in hearing the complete story of Paul and Dulcinea? Watch the video (nominated for Best Short Film at the 2021 Vail and Portland Film Festivals) for more info.

Want to be the first to know about every exciting new project at the Kirby Foundation?

Join Our Mailing ListBuild the life you love. Learn more about fusioneering:

Why pick which passion you should follow? Fusioneering allows you to cultivate many interests into something innovative and revolutionary.

Meet Paul and explore how blending your interests can empower you to follow your enthusiasm and bring your passions to life.