Get Inspired

Build the life you love. Learn more about fusioneering:

Posted on July 25, 2022 in AI Technology

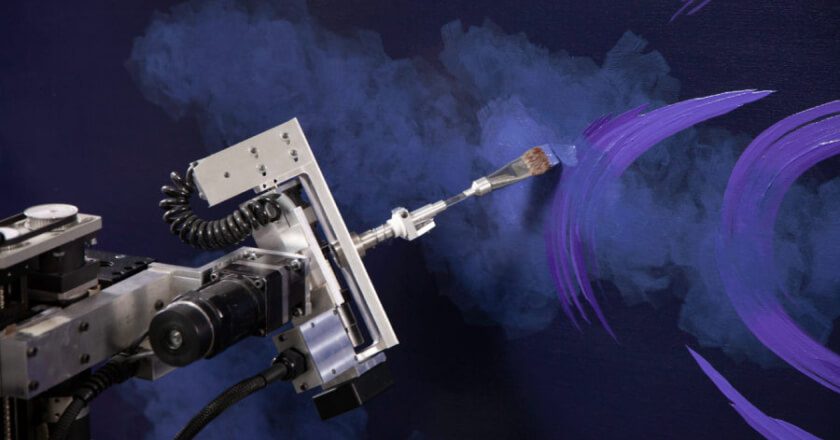

Paul Kirby’s robot painter, and the amazing AI systems behind it, have challenged notions of what a machine can and can’t do… but that’s typical for the field of artificial intelligence. As algorithms and machine learning become ever more present in our daily lives, it’s incredible to look back upon the history of artificial intelligence. Our modern existence… well, it started as a wild idea.

The concept of artificial intelligence found life long before computers. Humans throughout history contemplated the nature of existence, consciousness, and creation, and it’s only natural that from those musings came a variety of myths and art. Intelligent beings created through artificial means feature prominently in many belief systems, like the Norse figure, Kvasir (a being made from the spit of the gods), the Greek automaton, Talos (a metal man forged to protect Crete), or the Jewish folklore figure of the golem (a clay being made to serve a master). Examples in popular media abound, beginning in the modern era with popular portrayals in Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, Frankenstein; Czech writer Karel Čapek’s 1920 science-fiction play, R.U.R.; and Fritz Lang’s 1927 German expressionist film, Metropolis. The ethical quandaries and risks associated with artificially intelligent constructs have long been on the mind of the human race, and serve as a fascinating mirror into our own struggles with autonomy, existence, and our place as creators.

Related: How a Victorian Countess Defined Modern Computing

In the 20th Century, the concept of artificial intelligence finally became a real possibility. Advances in the theory and understanding of mathematics, coupled with formalized study of reason and logic – building on the work of philosophers from antiquity through the turn of the 20th Century – allowed computing pioneers to arrive at a “theory of computation.” This understanding was developed by titans of the age like Alan Turing and Alonzo Church, men who later posited that a machine could simulate any and all mathematical deductions using just a representative system of symbols. The system could be as simple as two separate symbols – such as a “0” and a “1”. This revelation is known as the “Church-Turing thesis,” and its incredible implications moved machines from being “calculators” to being true “computers.” Machines were no longer able to merely complete arithmetic processes (as with Charles Babbage’s original 1820s proto-computer, the “Difference Engine”), but were now capable of applying and understanding complex systems of rules.

In 1950, Alan Turing, knowing what the final outcome of his research would be, published the idea of the “Turing Test” (originally called the “Imitation Game”). The Turing Test was a simple evaluation of computer intelligence, designed to see if a machine could reasonably fool a human into thinking that the machine, too, possessed human intelligence. In the paper in which Turing posted his Imitation Game, he also made a major defense for a radical idea: machines can think. Turing asked his audience to redefine the idea of what “thinking,” a somewhat nebulous concept, truly meant.

In the 1950s, after Turing’s incredible computing victories over the Axis Powers in WWII, scientists began to consider if an artificial “brain in a jar” could be created. Two schools had emerged regarding how machine intelligence could be achieved.

The “Symbolic AI” approach sought to recreate the way the human mind works. Parties using the symbolic school of AI sought to recreate human-like systems of logical processes and semantics within computer language. The competing approach to machine intelligence was known as the “connectionist approach,” which attempted instead to more closely emulate the workings of the human brain. The connectionist approach sought to create artificial neural networks that behaved similarly to the networks of neurons in the brain. The symbolic approach to AI dominated from the 1950s until the 1990s, but recent developments in the 21st Century have allowed for connectionist ideas to gain new traction.

In 1956, an AI workshop was held at Dartmouth College, and the field of artificial intelligence was officially founded as an academic discipline. Computers from the Dartmouth workshop were shown to be able to solve algebra word problems, learn English, play checkers, and more – results that were stunning to the modern audiences of the time. Press coverage of the workshop created a media frenzy, and by the 1960s defense departments and labs all over the world had established research programs into artificial intelligence. Many scientists in the field believed that the creation of a full-blown artificially intelligent machine was right around the corner. Unfortunately, by the mid-1970s, many colossal technological constraints and limitations severely hindered progress. In 1974, the U.S. and British governments eliminated AI project funding due to budget considerations. This would later be known as the “AI winter.”

In the 1980s, computer technologies advanced significantly. One area of advancement was in “expert systems.” Expert systems are computer programs designed to mimic the thought process, logic, and decision-making of real human experts. Instead of conventional procedural code, expert systems employ “if-then” rules to reason through existing knowledge in order to solve problems. Implementing these expert systems was a widespread commercial success, reinvigorating the dying field of AI research and development. By the mid-80s, AI technology had become a billion dollar industry. Japanese government efforts to produce an $850 million dollar, “Epoch-making” AI supercomputer revived global government funding of AI research, but various failures (like the collapse of the Lisp Machine market) led to a second, longer, AI winter.

AI and robotics researchers of the late 80s expressed criticism of the dominant, symbolic approach to AI development. Advancements in human neuroscience and cognitive psychology revived interest in the connectionist approach to AI. This shift in focus led to the creation of many important “soft computing” tools, such as neural networks, fuzzy logic systems, and evolutionary algorithms. By the late 1990s, AI was once again the belle of the technological ball, and by the millennium, systems produced by AI research were widely used in computing.

Improvements in computing speed and cost, coupled with the explosion of big data, allowed for incredible advances in machine learning. Computers could now intake and process massive data sets, and by 2015, Google had more than 2,700 AI projects in development.

And that brings us to today, where the history of AI technologies – emboldened by cloud computing, deep learning, and more big data – continues to be written. While the initial goal of a “fully intelligent machine” has yet to be met, the field of AI research has had incredible, far-reaching impacts on much of society. A 2017 survey reported that one-in-five companies had incorporated AI processes in some aspect of their business, and in the period from 2015 to 2019, published AI research increased by 50 percent. We live in an AI-run future many said humanity would never see.

What breakthroughs will happen next? Maybe you’ll make the next great discovery.

Find out how you can fusioneer your own future, and follow the Kirby Foundation on Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn for more AI and interdisciplinary insights. If you can’t get enough, join the mailing list to ensure you never miss a beat!

Are you interested in hearing the complete story of Paul and Dulcinea? Watch the video (nominated for Best Short Film at the 2021 Vail and Portland Film Festivals) for more info.

Want to be the first to know about every exciting new project at the Kirby Foundation?

Join Our Mailing ListBuild the life you love. Learn more about fusioneering:

Why pick which passion you should follow? Fusioneering allows you to cultivate many interests into something innovative and revolutionary.

Meet Paul and explore how blending your interests can empower you to follow your enthusiasm and bring your passions to life.