Get Inspired

Build the life you love. Learn more about fusioneering:

Posted on September 14, 2022 in Art History

What is the function of a painting? Is a canvas meant to tell a defined and dramatic narrative, utilizing the most realistic forms… or can a painting merely be meant to capture the feeling of a moment before it yields to time?

Today, with abstract art of all sorts and postmodern reinterpretations of artistic meaning, most people are aware that “anything” can be considered “art” – as long as the art in question achieves any sort of emotional effect. But in the 1860s, art was thought about very differently. Claude Monet, one of the most celebrated painters of all time, was viewed as a hack… and then as a revolutionary. All this because, as he put it: “I want to paint the way a bird sings.”

Impressionism is an art movement and style of painting that originated in France during the mid-to-late 19th century. The style is characterized by small, thin – but still visibly accentuated – brushstrokes, open composition, unblended colors, ordinary subject matter, and – most importantly – a strong emphasis on the human perception of light and its interactions with the world. Impressionist paintings often seek to render the passage of time using light, and to convey the atmosphere of an experience rather than a realistic depiction of a locale.

In the mid-19th century, the French Académie des Beaux-Arts was at the center of the Western artistic world, with its Paris Salon art exhibition being seen as the pinnacle of all new fine art. The French academy held strict standards for painting content and style. Paintings exhibited at the Salon (whose artists were awarded prizes, connections, commissions, and recognition) were required to appear realistic upon examination, employing blended brushstrokes and muted colors. The paintings of the Renaissance were the ideal of the time. Religious and historical imagery were favored, while landscape and still life painting were viewed as remedial subjects.

Learn More: How Impressionism Evolved Into Abstraction

Four young and ambitious painters of the time and later, impressionist artists – Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille – were among those artists fed-up with the Academy’s restrictive view of the arts. The group had little interest in painting Biblical scenes or ancient history, and instead preferred painting the captivating natural beauty around them. The artists would regularly travel to the French countryside together to make art in a way that was nearly unheard of at the time: painting on-location. They painted in nature, unremoved from their subject, and captured the light and movement they witnessed firsthand. With this technique, and utilizing new and improved pigments that had come available at the turn-of-the-century, the artists were able to produce lighter, brighter, and more lively works than their contemporaries. Their painting evolved to focus on the enchanting and heightening qualities of light.

Learn More: Watch “Brushstroke” to learn about the Intersection of Art and Technology.

Roughly half of the work submitted by the group to the Paris Salon was rejected. Édouard Manet’s 1863 painting, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, was rejected from the Salon on grounds of indecency for depicting a nude woman sitting beside two clothed men – despite the fact that the Salon Jury had no issues accepting nude depictions of historical or religious subjects. Manet’s fans were furious over the Jury’s strongly-worded letter of refusal.

Emperor Napoleon III, in response to backlash from the artistic community, exhibited the works refused from the 1863 Salon at a “Salon des Refusés,” or “Salon of the Refused.” Despite attracting more attendees than the Paris Salon, requests to make the exhibition of refused art a mainstay was denied. In response, in 1873, Monet, Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas, and other artists founded the “Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs,” or the “Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers.” This new art society would exhibit the works of its artists independently, as long as its members forsook the Paris Salon.

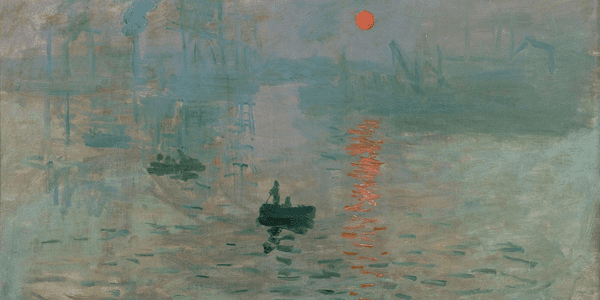

The new artistic society’s first exhibition was rocky. Critical response to the art movement was mixed, especially in regard to the works of Monet and Cézanne. Art critic, playwright, and humorist Louis Leroy wrote a cruel and scathing satirical review. In the review, he derided Monet’s painting, Impression, soleil levant, saying:

“Impression – I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it … and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.”

His article was entitled, The Exhibition of the Impressionists. While Leroy meant the term in a mocking manner, it quickly gained favor with both the public and many Impressionist artists themselves. Ironically, the name was a good fit, and accurately spoke to what many of the artists of the movement were trying to do: they did not seek to paint a place or a moment, but rather the impression such things leave.

Learn More: Who Is the Kirby Foundation?

The evocative and mesmerizing beauty of the new form, along with the incredible talent of its leading artists, won the doubters over. Impressionism rapidly grew in popularity, and soon became the expressive and spontaneous style most synonymous with the “new” and “modern.”

By the late 1800s, Impressionism had become a mainstay of the official Paris Salon, and to this day, Impressionism serves as not only a ground-breaking turning point for all modern and postmodern artistic movements, but also as an enchanting and enduring art form all its own.

What other art movements shaped the world, and how is art continuing to evolve? Does AI have a lasting place in the art world? Watch “Brushstroke” to learn about the intersection of art and technology and follow the Kirby Foundation on Instagram and Facebook. Be sure to join the mailing list as well to discover even more about painting, technology, and inspirational endeavors.

Are you interested in hearing the complete story of Paul and Dulcinea? Watch the video (nominated for Best Short Film at the 2021 Vail and Portland Film Festivals) for more info.

Want to be the first to know about every exciting new project at the Kirby Foundation?

Join Our Mailing ListBuild the life you love. Learn more about fusioneering:

Why pick which passion you should follow? Fusioneering allows you to cultivate many interests into something innovative and revolutionary.

Meet Paul and explore how blending your interests can empower you to follow your enthusiasm and bring your passions to life.