Get Inspired

Build the life you love. Learn more about fusioneering:

Posted on October 5, 2022 in Art History

Capriccio: the artistic term for where architectural structure meets and is transformed by an element of fantasy. Etymologically, the word comes from the old Italian word to describe “unpredictable movement.” Do you feel the movement of Capriccio?

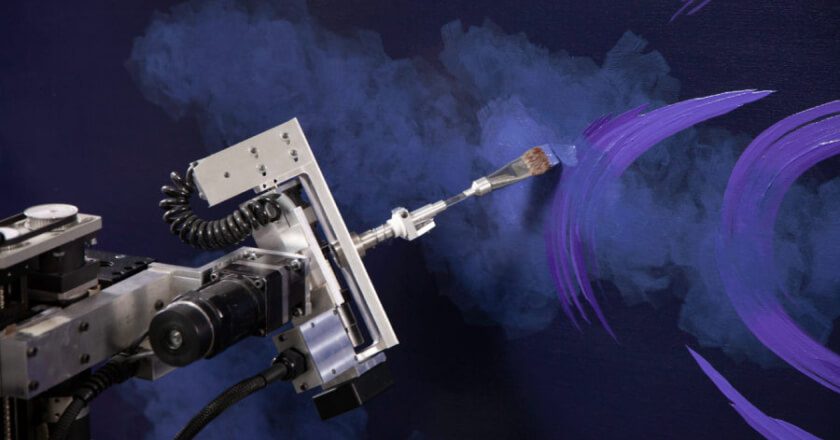

Discover how Paul Kirby and robotic painter Dulcinea drew on classical painting styles and palettes, alongside modern computing power and improvisation, to shape a journey for the eye.

Related: How Paul and Dulcinea Make a Painting

In the summer of 2006, Paul Kirby took an artists’ trip to the Anders Zorn Museum in Mora, Sweden. Zorn is regarded as one of the nation’s greatest painters, and the state-run museum serves as a showcase of both his studio and his captivating body of work. It was here the initial stirrings of Capriccio first came to be.

Something interesting about Anders Zorn was his adherence (across most of his paintings) to a single, limited color palette. Those colors, now known as the “Zorn palette” or “Apelles palette,” are yellow ochre, ivory black, flake (or titanium) white, and vermillion. Using just these colors, Zorn was able to create a wide scope of vivid and striking paintings, including celebrated portraits of presidents and kings. Paul, spellbound by the aesthetic and possibilities of the Zorn palette, decided that it would be used for Dulcinea’s next painting.

Vermillion (a shade of red) is the brightest color used in the Zorn palette. But Anders Zorn wasn’t the only inspiration behind Capriccio’s usage of the color. Edgar Degas, a realist painter and one of the founders of Impressionism, was fond of red in his works and would use the color to break up scenes and guide the eye. Paul had become interested in Degas’ use of red after seeing his paintings at an exhibition of the Copenhagen Museum. Paul’s goal was to employ red and the muted Zorn colors as means to guide the viewer through Dulcinea’s piece… but more on that below.

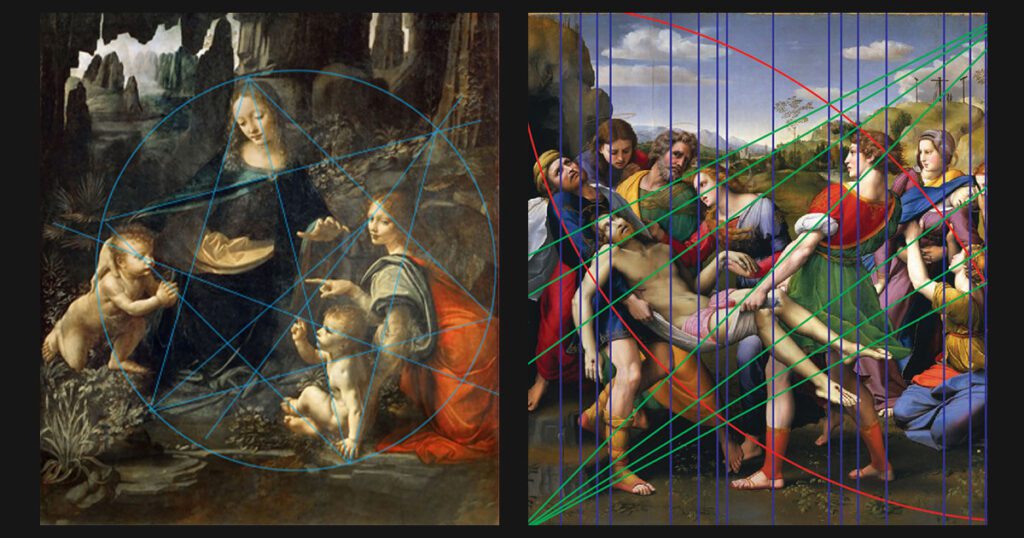

Paul Kirby has long been fascinated with classical Renaissance painters. The works of da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo, and other artists of the period heavily emphasized harmony, balance, proportion, and symmetry. One strong and pervasive structural element of works from the period is the presence of distinct forty-five-degree angles to create visual flow. These angles are easily observed when looking at most large, classical paintings, though they manifest in many forms, be it an arm, spear, sword, flowing cloth, or outstretched leg. This use of forty-five-degree angles would form the structural basis of Capriccio.

In the later years of the Italian Renaissance, a new style emerged in response to the over-adherence to visual unity: Mannerism. The Mannerists sought to create elegant and engrossing compositions with exaggerated features and compositional tension – like asymmetrical positioning or warped proportions. Evoking these inspirations, Paul wanted Dulcinea’s next painting to be an engaging asymmetrical structure of curves and colors that took the eye on a tour across the canvas. Capriccio’s large curve takes you to the upper right corner first, then the reds cause the gaze to jump to the left corner and draw it down counterclockwise back around through the scene.

But on top of all this art theory, how did Dulcinea know what to paint?

The emergent artistic surprises that arise from AI programs are one of Paul’s favorite parts of painting with Dulcinea. Paul relishes the spontaneous elements that come from simulation.

If you’re familiar with Dulcinea, you’re familiar with Paul’s “ants.” These ants are really AI agents using complex adaptive systems to “think” and react to their simulated environment – and from these ants come the surprises that transform into Dulcinea’s brushwork. The ants rely on principles of stigmergy, a mechanism of indirect coordination for agents that allows them to react to traces left in the environment by other agents. Local interactions between agents and the environment lead to self-organization within a system, where order and structure form out of initial disarray.

In practice, it worked like this: in a virtual world, “breadcrumbs” were deposited along the structural guidelines for Capriccio. AI agent ants were given simple rules to discover breadcrumbs and deposit new “pebbles” at their locations. Ants were also instructed to deposit pebbles alongside the pebbles of other ants (within limits that prevented overcrowding). Stigmergy created an emergent order within the “ant colony.” Though the individual ants were unaware of each other’s existence, through environmental stimulus and response, they were able to operate with coordination. From their deposited pebbles, Dulcinea was able to produce brushstrokes that possess a dynamic, energetic, and spontaneous quality of movement.

And there you have it: ancient structures and ideas, transformed by the fantastical.

See where Dulcinea started, and join the Kirby Foundation on our Instagram, Facebook, and mailing list to discover where she’s headed next!

Are you interested in hearing the complete story of Paul and Dulcinea? Watch the video (nominated for Best Short Film at the 2021 Vail and Portland Film Festivals) for more info.

Want to be the first to know about every exciting new project at the Kirby Foundation?

Join Our Mailing ListBuild the life you love. Learn more about fusioneering:

Why pick which passion you should follow? Fusioneering allows you to cultivate many interests into something innovative and revolutionary.

Meet Paul and explore how blending your interests can empower you to follow your enthusiasm and bring your passions to life.